Photo by tazain bin alam on Unsplash

I

Where to Begin

It all begins with the wicket.

Three posts (actually called “stumps” or “stakes”), twenty-eight inches high and an inch and a quarter in diameter, stuck in the ground so that they stand vertically, and spaced so that a cricket ball would not have enough room to squeeze between them. Across the top of these are precariously balanced two dowels (called “bails”), so that the wicket forms a sort of fragile window frame, or a “gate.” A little, precious, precarious rectangle that a strong breeze might knock over, but that would definitely topple if struck in any way, particularly by a cricket ball.

The object of all play is then essentially for the offensive, or batting, team to keep the wicket from being upset, and for the defensive, or fielding, team to knock it down. Everything in the game emerges from there. Hopefully, realizing this can help make sense of much of what is happening on the field.

II

The Playing Field

Cricket is a game played in the round. Unlike baseball, there is no foul territory, only, if you will, the playing field within the boundaries and the crowd outside (think of it as all being the left, center, and right field walls—where home runs got to become fan souvenirs—all the way around). The space within the boundaries will vary depending on the confines of the stadium, but it’s typically somewhat circular between 450 and 500 feet across.

Because of the wear, sometimes there will be multiple pitches on the field to use. (Photo by AaDil on Unsplash)

In the center of this large space, there are a pair of wickets, placed twenty-two yards apart (oddly, almost exactly the same distance as between the pitching rubber and home plate), measured from the center of each middle stump.

In front of each wicket is a box created with chalk lines that define, on one side, the area where the batter bats (think of it like a square home base where the batter stands, and on the other side, how far the pitcher or “bowler” can advance before releasing the ball. These boxes, and the lines that create them, are called the “crease.” (This is relatively more complicated than this, as there are different names for different crease lines and different areas of the crease, but for now, just think of the crease on one side as where the batter’s “box,” and the crease on the other side defining the line before which the bowler must release the ball for it to be a legal “pitch.”)

These create a relatively small rectangle in the middle of the pitch (roughly twenty-five yard long by five yards wide) where much of the action of the game takes place. This is called the “pitch,” which would make sense to baseball fans since it is sort of where the “pitching” happens. Just to confuse things, however, it’s not called pitching, but “bowling,” so feel free to go back to feeling befuddled.

Around this area is a smaller circle within the larger field that is called the “infield” (finally a similarity that sticks!). This area is roughly oval. (If you drew circles around the wickets with diameters of fifteen yards and then joined the edges surrounding the pitch with straight lines, that would form the infield.)

III

How the Game Is Played

Given this setting—a big, circular field with a relatively small oval infield in the approximate center, with the pitch in the center of that—play goes like this: the pitcher (called the “bowler”) throws the ball in an attempt to upset the wicket. The batter, by contrast, uses the bat (a flat sort of plank like thing that is on the end of what looks almost exactly like a baseball bat handle—something that might function well as a canoe paddle, in a pinch) to protect the wicket.

Storm and fix that in your mind for a moment. The bowler wants to knock the wicket over with the ball, the batter’s job is to protect the wicket with the bat. At the release of every ball bowled, that’s the essence of what’s happening. Either the batter survives or the bowler wins with each throw. Everything else that happens on the field is additional to that one on one duel.

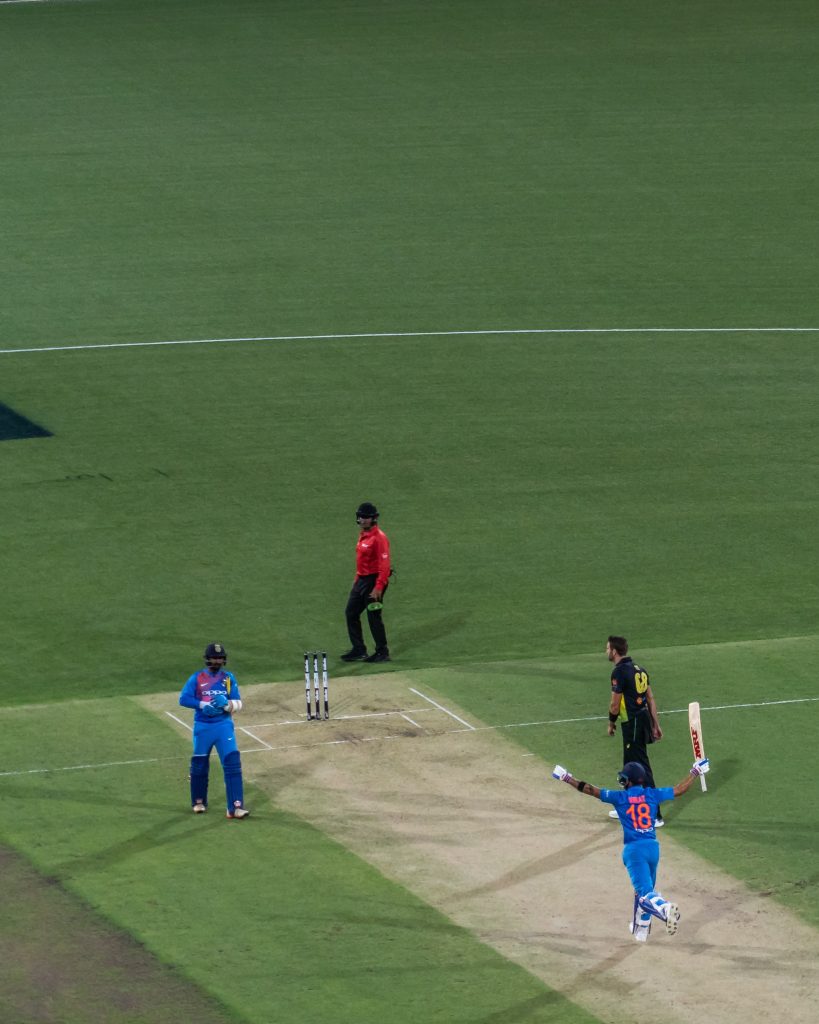

As long as the batter protects the wicket, he/she keeps batting (there are actually two batters at a time, but I’ll get to that). If the wicket is hit, the batter is out and replaced by another until every member of the team has batter. When this happens, you’ll usually see the pitch parade in some form of ecstatic celebration. Though it is the equivalent of a strike three in baseball, it is far less common and far more difficult to achieve since even a block with the bat is enough to keep the batter in the game. Once a batter is out, though, they don’t bat again in that game, or “test,” given the type of match it is. Teams only bat once through the lineup, first new team, then the other.

At the same time, it’s not uncommon for a batter to stay in the game and score 50 (called a “half century”) or 100 (called a “century” for obvious reasons) or more runs. It’s an accomplishment requiring some cunning, skill, and stamina, but it does happen. It’s also possible, and happens more often, that a batter is put out before she/he even scores one run. That’s just how the ball bounces.

And, yes, that’s another big difference. Bowlers can bounce the ball before it gets to the batter, hoping to confuse the batter, cause them to miss it, and sneak it by them to hit and topple the wicket. I don’t think it has to bounce, but I’ve never seen a throw that didn’t. The release of the ball from the hands is also very different. Typically a bowler grips the ball with the whole hand, not just certain fingers, and releases it with the whole hand coming over the top of the ball. It literally gives the game a completely different spin.

Not only that, but bowlers don’t stand in one place to bowl (throw) the ball, but can run up to their crease, and as long as they release the ball before they step over the crease, it’s a legal “bowl.” Thus some bowlers add the equivalent of a 40-yard dash before they release the ball, starting way out in the field and run, run, running up to the crease to release it at the last second before stepping over the crease line. Consider it added anticipation or consider it a waste of time, that’s up to you. It’s one of those, “It is what it is” things.

IV

Scoring

Runs are scored by the batter putting the ball into play and running to the opposite chalked square (“crease”) in front of the opposite wicket, as if it were a base. Thus cricket has two bases and reaching one safely (or you might say, “not out-ly”), scores a run. There and back to the first crease is two runs, and so on. Theoretically you could do that all day if the ball kept bouncing around between players, but usually no more than three runs are scored at once, usually fewer.

A local Sunday club match here in Colombo. (My photo)

Batters do not have to run, because if they leave their present crease for the other, the wicket is vulnerable to any player on the field hitting it with the ball and getting them out. As the batters exchange creases (remember, I said there were two, and while one bats, the other stands by the crease of the other wicket to “protect” it, and then exchanges creases with the batter to score runs), fielders can take the ball and throw it to hit the wicket or “tag” the wicket with it to upset the wicket, in which case the batter would be “out,” and the fielding team would be awarded a “wicket.” (You know, called the same thing just so one think in the game would be simpler to follow.)

Thus you see score lines like 123-3 in the middle of a match, which is to a blowout score, but only the score for half of the game. It represents runs to wickets. (There will be a separate runs to wickets score for the other half of the game.) in the example above, 123 represents the runs for the batting team, and 3 represents the wickets for the fielding team, which also means three batsmen have been eliminated from the batting side.

V

Balls that Leave the Playing Field

There are two situations where the batting team scores without running, and that is when the ball hits or bounces over the boundary, or the ball flies over the boundary in the air.

If the ball hits the boundary or bounces over it, it is counted as a “four,” and four runs are awarded to the batting team. If the ball goes out in the air, equivalent to a home run in baseball, the team scores a “six.” (Strangely generous scoring compared to baseball, of course, but now you can see why scores tend to be in the hundreds.)

Because there is no foul territory in cricket, a four or a six can be scored off of what would be a foul ball in baseball. This makes for what will often look like a happy accident to a baseball fan. (I think my favorite is where the batter sort of catches the ball, it rolls up along the bat bottom to top, and then goes into the crowd behind him for a six. It feels like a total cheat to my baseball sensibilities, which sort of makes it all the more fun.)

VI

“Outs” or “Scoring a Wicket”

When balls remain in the field of play, things get a bit more interesting (just like in baseball). Any batter not in a crease with at least part of their body is vulnerable of being put out.

If a ball is caught in the air, just like in baseball, the batter is out. End of story. A fly out in both games is exactly the same.

If the ball touches the ground, however, then batters can score as many runs as they can get back and forth between the two wickets before a defender can upset the wicket with the batter outside of the crease. (Did you get that? I know that sentence is a mouthful!)

This creates situations similar to a batter sliding into a base or across home plate. Fielders try to throw the ball to hit the wicket or be caught by another player who will take the wicket and knock the wicket down before the batter can get any part of their bodies “across the crease.”

In a weird difference to baseball, bats are considered part of a batter’s body, so you will often see runners extending their bats across the crease to avoid an out in the same way a player would slide in head first to a base. Note again: you don’t tag the batter/runner with the ball, you tag the wicket. If the batter/runner is in the crease, the batter/runner is “not out.” If they are outside the crease when the wicket flies to pieces after being struck with the ball, they are “out.”

Yes, you are reading that right, the runner/batter is not tagged, but the wickets is knocked over, which can happen with a throw or a ball in a hand swept through a wicket.

VII

Close Plays and Instant Replay

If the play is close, instant replay, is called upon to help the officials decide the right call, just like in Major League Baseball. Cricket, however, has taken instant replay to a whole new level beyond what baseball has accomplished.

In the MLB (or football, for that matter) [American football, not soccer, right. Can I get and Ay!” from the Canadians?]), once you see a definitive angle and feel you know what the call should be, the anticipation is over and the rest is just a delay of the game. In cricket, however, they add graphics and layers to instant replays. Each part of the play gets its own ruling, all of which must line up for the player to be out. Was the batsman back over the crease in time? Out or not out. Did the ball contact the wicket? Out or not out. Was the wicket actually moved enough to upset the bails? Again, out or not out. (This is taken to its highest drama in the case where a batsman blocks a ball with their body that would hit the wicket except for them getting in the way, another discussion for a bit later.)

As each part of the play is analyzed and decided, the crowd is on their feet watching for the next element to be judged. Each part of the decision gets its own little box, and each one that reads “out” builds anticipation. If one is determined “not out,” the analysis ends and we get back to play. Kind of ingenious, if you ask me. (This also seems to be more dramatic in countries where decisions by society and government can seem more arbitrary and unpredictable, so seeing is not necessarily believing, but that’s a different discussion.)

VIII

Game Length and Structure

Structurally, each game has two halves. The first half, one team bats and the other fields. The second half, they switch. The game ends when the team that bats second either scores more runs than the team that batted first, or the last batter of the second half is out before they reach the number of runs gotten by the team that batted first, or a maximum bowl limit is reached before the team that batted second scores more runs than the first-half batters did. To say that more simply, the team that bats first gets as many runs as possible, and the team that bats second tries to surpass their score. (So why do scores keep track of wickets, then, you may ask? Honestly, I have no idea.)

Sri Lanka wins! (Photo by Mudassir Ali on Unsplash)

So, as it’s good in baseball to bat second, it is even more so in cricket. The team batting first just scores as many as they can; the team batting second has an exact goal. Because of this advantage, batting order is decided by a coin toss at the beginning of the game rather than the hosting team batting last, more like how football (again, not soccer) decides who kicks or receives at the beginning of the game.

Thus, like baseball, games are historically open-ended and do not have a time limit, which is why some cricket games have taken days to complete. (The longest cricket match ever, according to The Guinness Book of Records, was between South Africa and England in 1939, lasting forty-three hours and sixteen minutes, and spread out over twelve days. When it rained after tea on the twelfth day, the teams agreed to end the match in a draw rather than pushing it to a thirteenth day. One player scored a double century. It sounds like it was quite a match.) Today, however, different formats are used that limit the number of pitches and keep games more to a manageable three or so hours, more like an MLB game. The T20 is a popular short-form “test,” and a best of three T20 is often played before a more traditional five-day competition.

Within the halves, play is broken up into “innings,” which are six bowls (pitches) each and have nothing to do with outs. At the end of each inning, the bowler is switched out. Bowlers can bowl more than once in a half, but not twice in a row. Bowler changes create little mini breaks in the game that seem perfect for TV, which fit a commercial into each of those gaps (though I have to admit, it would be great if it wasn’t always the same commercial).

IX

When the Game Gets Interesting

After getting down these basics, the patience to what a full match will probably still elude most baseball enthusiasts (at last it did me). So, at first, I watched a bit in a bar filled with Sri Lankans who were so enthusiastic for the match, they even stood as their national anthem as played. That was fun for a bit, but these are fans with more endurance than I have.

So next I just watched the highlights the next day on YouTube. That way I caught all the actin, but none of the live enthusiasm. So, now, I try to measure out my time so that I can watch the last fifty bowls or so, which is a little like watching the last two or three innings of a MLB game. It’s enough to give the match some context, and as the pitch could not lowers and the run count increases towards the number of runs needed to win, anticipation grows to thrilling heights. When a team is down to its last bowl and the batting team is four runs down, you can imagine the tension and pressure on both bowler and batter. Watch it in a country that cares about cricket, and it can almost make up for the fact that the real game you love, baseball, is mostly played while you sleep. (A 12.5-hour time difference is no joke when it comes to watching live sports.)

X

All the Rest

The essence of the game. (Photo by Patrick Hendry on Unsplash)

With this much knowledge, you can watch a test and follow most of what is going on, but you might want to turn the sound off. In addition to the actual game play explained above, the commentators will throw all kinds of statistics at you that you have no clue either the point of or what they mean. Like baseball, they have other ways of measuring the efficiency of a bowler one batter, similar to baseball’s ERA, WHIP, RBIs, or Slugging Percentage.

For the more serious enthusiasts, I’m sure these help with the enjoyment of hours of discussion all-time great players and teams and who will win this years championship. For the more casual person just looking to enjoy a sporting event, dance around in the stands, and hopefully see themselves on the big screen display in the stadium (which sort of looks like every Sri Lankan in a crowd at a match who seem to be enjoying themselves regardless of what is actually happening on the field), the above is enough to get you started, let you enjoy watching the last fifty bowls, and even make you slightly interested in one day going to a match. Cricket is a happening unique unto itself, and some of it even has something to do with the game on the field.

Hopefully this is enough to help you enjoy the action of a game if you get a chance to watch a bit of one (or, like I have experienced, there are literally no other live sporting events to be found). As far as which is better and all that, I’m glad to meet you in a Sri Lankan bar with a TV near a beach, and we can debate with some true believers. I can guarantee you of one thing, at least you will enjoy being at a beautiful Sri Lankan beach.

Recent Comments