There is a Chinese curse which says, “May he live in interesting times.” Like it or not we live in interesting times. They are times of danger and uncertainty; but they are also more open to the creative energy of men than any other time in history.[1]

—Robert Kennedy

Cape Town, South Africa

June 1966

[Originally posted: July 19, 2022 / Updated October 27, 2022]

By all accounts, it appears we embarked on our year-long visit to Sri Lanka in some of the most interesting times the country has ever experienced, and that’s saying something for a not-so-small island with almost 3,000 years of civilization, three decades of a bloody, racist civil war, having communities devastated by the 2004 tsunami, and which found itself in the crosshairs of terrorists on Easter 2019 when suicide bombers attacked a number of church gatherings and luxury hotels, killing 269. The ghosts are enough to dissuade you from this being a good place—the natural beauty and the overly friendly people speak of a paradise completely separate from its traumatic history.

A depiction of the Kandy Perahera, one of Sri Lanka’s most colorful traditions.

But I suppose the worst economic crisis in the country’s history; mobs of tens of thousands of unarmed Sri Lankans infiltrating and occupying the President’s House, the Presidential Secretariat, and eventually the Prime Minister’s offices; the president and his family fleeing and him resigning just a few days later would indeed trump all of those things. In a mere two weeks, Sri Lanka experienced its own Arab Spring and January 6 all rolled into one. At that point (July 2022), the country was facing the formation of its fourth government in less than five months.

To unpack how all of this came about, it’s hard to know where to begin. As a former Commonwealth nation (that was controlled by the Dutch (1658-1796) before the British, and the Portuguese (1505-1658) before the Dutch), Sri Lanka still lives with a lot of the baggage that comes from colonialism. You might think seventy-five years would be enough to change things, but when China’s current largest international effort is to rekindle its glory days of the Silk Road (its Belt and Road Initiative), national identity seems to change far more slowly than technological progress would make you think. (Old wine in new wine skins?)

Sri Lanka in the Twentieth Century

Sri Lankan independence officially came on February 4, 1948, just months after India’s and just months before Israel’s. As a country that had been exploited from the time of the Reformation, however, it feels like certain cultural and social-economic inequalities must have remained ingrained despite independence. All the same, Sri Lanka was the second richest country in Asia at that time with only Japan having a better economy. The Sri Lanka of early independence was a land of racial integration and secular prosperity. It is common knowledge here that Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew came to Colombo in the early 1950s and hoped that perhaps one day Singapore could hoped to be as developed. It is even said that he adopted “The Colombo Plan” for development in Singapore and followed it to the letter, a plan that was never implemented in Colombo itself. At the time, Colombo was a prosperous city of beautiful open gardens and palatial homes left by the British. Unfortunately, that is far from the case today. (The civil war turned it into a maze of walled compounds, and I’m pretty sure, behind those walls, the gardens have been forgotten.)

In the days before independence, Sir Lanka looked like a unified front both ethnically and religiously, coming together to form its own constitution and cooperating in the process toward self-rule. That doesn’t seem to have taken long to fall apart. In the years before and after independence, Ceylon (as the island was officially called until 1972) was ruled by a secular elite more interested in its advancement that its wealth. The Sinhala majority, Tamil minority, and conglomeration of smaller groups of Burghers, Muslims, Catholics, and others seemed to coexist in relative harmony. Treated evenhandedly, Ceylon looked to have a bright future.

However, in this religious/racial melange, there was a uneasiness that could be exploited. The early Ceylon leaders seemed to know that leveraging the seventy-some percent Sinhala Buddhist majority would have dire repercussion, but for others it was too quick a path to power. The Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) decided to take advantage this majority for their own purposes and began campaigning with policies that would favor this Sinhala majority to the exclusion of all others to the point that a “Sinhala only” policy was adopted in 1956 making Sinhala the official language of Ceylon above Tamil and even English. Tamils and other ethnicities effectively became second class citizens overnight. If there’s a Buddhist equivalent of Pandora’s Box, at that moment, it was thrown open and Ceylon was about to emerge from a peaceful childhood into a horrifyingly traumatic adolescence.

In 1959, due to his feeling that a promise to him for his political support was unfulfilled by the SLFP Prime Minster, Buddhist priest Talduwe Somarama Thero assassinated S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike during a public meeting at his home residence, Tintagel (which is now a rather upscale restaurant). The SLFP made Bandaranaike’s widow, Sirimavo, the new head of party and she became the first female Prime Minister in the world in 1960. She would serve as Prime Minister three different times, and it was under her leadership that a new constitution—which introduced the office of the executive presidency, changed the name of Ceylon to Sri Lanka, and separated it from the British Empire—was written and adopted. Sirimavo Bandaranaike because a major voice of the Non-Aligned Nations, defying the United States and the Soviet Union as the leaders of the only power blocs in the world.

The seeds of ethnic division were sown, however, and the violence of an unhappy Buddhist priest seemed to set an example for how disputes would be address in Sri Lanka for decades to come. A coup was unsuccessful in 1962. In 1971, the communist Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) tried to have their own revolution, which failed, but would have repercussions for years as suppressing them with an iron fist because the preferred modus operandi of government for dealing with all of its opposition.

In the mid 70s, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam[2] (LTTE, also called the “Tamil Tigers”) formed and began a campaign of violence calling for the creation of a separate state in the Northern and Eastern parts of the island. (They were not the only group to do this, but through violence against their rival Tamil groups as well as the Sinhala majority government, they eventually became the face of the cause.) A series of ever increasing tit-for-tat acts of violence—including the burning down of the Jaffna Library, losing hundreds of irreplaceable ancient texts, and riots in the streets of Colombo that led to the murder of more than 3,000 Tamils—eventually led to a civil war in 1983.

The Tsunami and the End of the Civil War

The civil war was still dragging on when the tsunami from an earthquake near Indonesia sped across the Indian Ocean and hit the eastern, northern, and southern parts of Sri Lanka in 2004, killing 31,299. Another 4,093 went missing and 21,411 were injured. Entire communities had to be rebuilt. The wave changed the salinity of certain lagoons and ponds, changing the migration of storks and other birds, as well as increasing the habitat for aggressive saltwater crocodiles. Aid flowed in to help restore communities and what was rebuilt spanned from being slapped together “hideous corrugated iron boxes . . . shiny metal bomb shelters which probably work well as sun ovens during the day” to towns on the map that might be described as a “post-tsunami eco-village.”[3] It was a wound that would take time to heal.

It was in 2005 that the characters in our current drama took centerstage. Mahinda Rajapaksa had been on and off in Sri Lankan politics for thirty-five years already by this point, being elected to parliament in 1970 as the youngest MP at the age of twenty-four. (The Rajapaksa name was already well known at the time. His grandfather held a powerful post in British Ceylon, and his father was deputy speaker in parliament in the decades after independence.) Mahinda attended law school while an MP and when he lost his seat in 1977 to the same man he had beaten in 1970, he took up a legal practice as a criminal lawyer in Tangalle, not far from his home of Hambantota. In 1994, he rejoined the government and became Minster of Labor. In 2002, he became the leader of the opposition, and in 2004, he became Prime Minster while also heading up the Ministry of Highways, Ports, and Shipping, a short stint that caused a constitutional crisis which eventually forced him to resign just three months after he was appointed.

In 2005, Mahinda ran against Ranil Wickremesinghe (who he had replaced as PM) for president and narrowly won, perhaps because the Tamils called for a boycott of the election. If so, it was a major mistake for them. Mahinda appointed his brother Gotabaya, who had been in the military, as Minister of Defense and Urban Development, and together they built a reputation as strong-arm politicians who did “what was necessary” to end the civil war in 2009 (an estimated 100,000 died and there have been accusations of war crimes) and restore Sri Lanka to the world stage.

In many ways, the civil war put Sri Lanka into a time capsule. Development was put on the back burner while the government focused on defeating the Tamil rebels. Few countries were interested in investing money in a war zone anyway. While other countries advanced in the most prosperous decades the world had even known, Sri Lanka’s infrastructure languished while it’s jungles and forests remained all but untouched by tourist development. Once the war was brutally settled, the victorious government set its eyes on catching up. Mahinda called for early elections to take place in 2010 to solidify his position for the beginning of this new chapter and won relatively easily.

Despite historic problems, an already growing national debt (Sri Lanka borrowed heavily to finance its war efforts), and the 2008 global financial crisis, the future looked incredibly bright for Sri Lanka. To outside interests, Sri Lanka looked like a gem of an investment. Not only was it an unrivaled tourist destination for the richer counties west and north of it (especially when things got cold in Europe and Russia), it was primely located to service ships traversing the Indian Ocean and headed to and from the Suez Canal, a shipping lane that accounts for about eighty percent of the world’s ocean-borne trade.[4]

Catching Up on Infrastructure Beginning with a Port in Hambantota

To address this opportunity, among other projects, the Rajapaksa government dusted off an idea that had already been batted around a few times throughout the preceeding decade (likely even landing on Mahinda’s desk when he was Minister of Highways, Ports, and Shipping): building a second port on the southern coast of the island in the town of Hambantota, which also happened to be where the Rajapaksa brothers grew up.

In 2003, the Canadian International Development Agency concluded a study that such a port was feasible. A second report was done in 2006 by the Danish firm Romboll suggesting the port could be successful if done in phases, starting with non-container ships. This would take pressure off of the Port of Colombo along the west coast of the island that was nearing capacity. Container ships could go to Colombo and the others could be serviced in Hambantota, an area with more potential for expansion. To be profitable, Hambantota would only need a fraction of the business going through Singapore, the world’s busiest port along the same route to the east.

Before the war was over, in 2007, Sri Lanka approached the United States and India asking for financing to build the port. Both said no. China Harbor Group got wind of the project and started lobbying to obtain the contract to build it. When China Eximbank agreed to fund it for $307 million (eighty-five percent of the expected cost for the first phase[5]), construction began. (Note that Chinese leader Xi Jinping had not yet mentioned China’s Belt and Road Initiative. His first mention of it was in October 2013. So while many point to Hambantota being part of that, it wouldn’t have been when construction began, nor when phase I was finished). The first phase was finished on schedule and inaugurated on November 18, 2010. Mahinda took the liberty of naming the port after himself.

This was all well and good, but the thought seemed to be that if some development was good, more—a lot more—was better. The Rajapaksas apparently expected a bright future and decided to build for it. (The fact that they were getting kickbacks in the form of “commissions” for setting up loans may also have had something to do with it. Sources estimate these were adding up to somewhere between $120 and $500 million a year.[6]) On a roll they didn’t think would end, they also grabbed for more power. Using the strong parliamentary majority for their coalition, they added an eighteenth amendment to the Sri Lankan Constitution on September 8, 2010, that took power from parliament, the Prime Minister, and the cabinet to consolidate it in the executive presidency. The amendment also removed the presidency’s two-term limit.

If a Little Is Good, Isn’t a Lot Better? Creating “Bling”-frastructure

Five of the towers of downtown Colombo (left to right): the stair-stepped Altair, the Lotus Tower, the Hilton Residences (where we have an apartment), the Colombo City Center Mall and Apartments, and behind that, the three towers of the Tri-Zen luxury apartments which are still under construction.

Looking to create yet more infrastructure to pave the way for Sri Lankan growth into the decades ahead, they created government bonds that would pay 8.25 percent (reasonable at the time, but costly in the long-term), which were quickly snatched up by the West. They also borrowed another $757 million from China Eximbank in 2012 (at a notably better rate than in 2007, thankfully). Then, rather than letting things catch up and start paying for themselves, they decided to build a new highway between Hambantota and Colombo, as well as between Colombo and Kandy, pushed immediately into phase II in Hambantota to open it to container ships, built expansive government buildings to handle the forecast import duties and oversee the servicing of ships in Hambantota, a new airport in Hambantota, and just for good measure, a 35,000-seat cricket stadium in the town of 25,000. Many of these also received the “Mahinda Rajapaksa” moniker.

From a different angle, left to right: one of the two towers of the newly finished Capitol Twin Peaks, the still-under-construction Sri-Zen towers, and the Altair, finished a few years ago and still largely vacant.

Despite high hopes for all of these projects, none of these have made any real money (the Colombo-Kandy freeway only has one 49-kilometer section finished which didn’t open until Jan 2022), let alone looked to be able to service the loans that had created them. Mismanagement hobbled the port and it bled money. The port has a narrow entry way that only allows one ship to enter at a time, which requires tugboats—why most ships still opt for the port in Colombo.

Regardless, the decade of boondoggle projects (2010-2020) was launched in Sri Lanka both publicly and privately—it was as if people poured money in with the concrete and there it has stayed. Tourist investments seemed to pay off (bringing in roughly $4.4 billion a year until 2019, anyway), but not the high-rise apartment buildings that started popping up in Columbo as if it was to be the next Hong Kong. As I write this today, many of them stand empty, while some remain unfinished. It’s as if no thought was ever given to estimating return on investment before beginning to build.

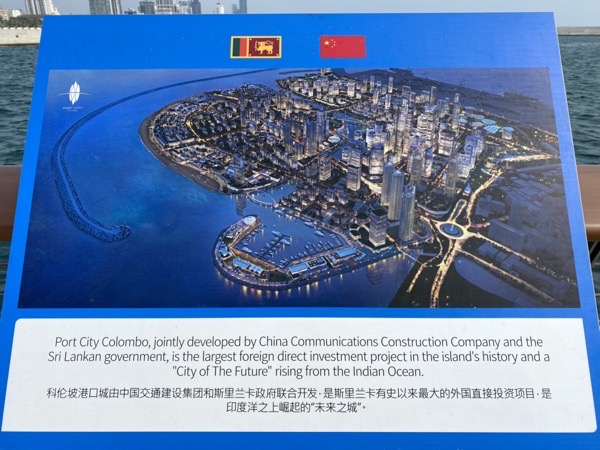

Other such projects include the Lotus Tower (begun in 2012) in an attempt to give Colombo a tourist site to rival Paris’s Eiffel Tower and a brand-new downtown area dubbed the “Port City” built on a manmade peninsula similar to Palm Jumeirah in Dubai. Port City today is a giant sandbar just north of Galle Face Green and west of Colombo’s primary business district. (Projects so egregiously unnecessary, some have labeled them as “bling-frastructure.”[7])

The Colombo Port City and The Lotus Tower

A pictorial representation of the ambitions for the Colombo Port City.

The Port City was scheduled to begin construction in 2011, but wasn’t started until 2014. It was designed to be the home of a Colombo International Financial Centre which would be a special financial zone where rents could be in any currency desired, though probably mostly US dollars. To get it built quickly, it would receive special tax and import duty incentives. It would become the home to luxury hotels, apartment buildings, commercial spaces, restaurants, a marina, a casino, retail outlets and shops, a convention and exhibition center, hospitals, schools, and whatever else would be needed for roughly 80,000 residents. The plan was for Colombo to rival other major port cities like Singapore, Mumbai, and Dubai and become the prime real estate of Asia. Planners estimated the project would bring in $15 billion over the next twenty-five years (when it would finally be completed). In exchange for $1.4 billion and taking on the construction of the island, CHEC (China Harbour Engineering Company) Port City Colombo was given a ninety-nine-year lease on forty-three percent (116 hectares) of the reclaimed land.[8]

The Lotus Tower across Beira Lake (from our apartment).

The Lotus Tower is perhaps the one most prominent of these projects to us since we look out on it from our apartment. When we asked around about it, the first thing most people mentioned was it was built with Chinese money. The large, lotus-bulb-on-a-stock building hosts a restaurant, viewing stations, and was supposed to be a major tourist attraction. It was finished in 2019, but has only recently opened to the public. (Still not ready for public viewing, in my opinion, but at least it’s finally making some income.) To have spent $104.3 million on that while vital thoroughfares between commercial centers seems at least a tad reckless. It’s lit up every night now between 6:30 and about 10:00 pm, longer if there is an event going on in its concert grounds. Supposedly it consumes about as much electricity as the rest of the city (which is an exaggeration, I am sure, but given the rolling blackouts Sri Lanka was forced to endure soon after we arrived, it seems tactful that they’ve left it off until they could end those.) Notably, it has been paid for by Sri Lanka and is not in Chinese control (unlike the Port City and Hambantota), but that only means its cost was diverted from something that would have actually done the country some good.

The 2015 Presidential Election

In 2015, confident of success and looking to secure the next six-year term to ensure he would be around to continue to build the Sri Lanka he envisioned, Mahinda again called for early elections. In a surprise move, just months before the election, his health secretary, Maithripala Sirisena, jumped ship and announced he would run against him, campaigning to end corruption and promising to add a nineteenth amendment to the constitution rescinding the eighteenth amendment (redistributing power among the branches of government), leveling claims of rampant corruption throughout the Rajapaksa administration and of the brothers catering to the Chinese and “selling it off” piece by piece. Sirisena narrowly defeated Mahinda, which was likely a surprise to everyone including Sirisena. (Colombo, the Tamil north, and the Hindu center of the country all sided against Mahinda.) Thus Maithripala Sirisena became president, Ranil Wickremesinghe became Prime Minister (for a third time), and the nineteenth amendment was quickly ratified, defanging the executive presidency.

Mahinda stayed on in parliament, however, and became Prime Minister for a short stint (less than three months) in 2018, replacing Wickremesinghe on October 26 and then being replaced by him on December 15. His tenure was so short because his appointment created a constitutional crisis and was judged illegal by many. Before things rose to a boiling point, Mahinda stepped down and Ranil was reinstated.

In attempts to deal with the rising debt and growing government and military expenses, the Sirisena government raised taxes, froze the construction of the Port City, and looked for a contractor to take over the management of Hambantota. In 2017, the Hambantota International Port Group (HIPG) was formed, and China Merchants Ports invested $1.12 billion to claim an eighty-five percent interest of the group. HIPG was award a 99-year lease after which the management of the facility would return to the Sri Lanka Ports Authority. Sri Lanka chose to add the $1.12 billion to their foreign reserves rather than to pay down any debt.

The Rajapaksas Return to Power

In early 2019, even with tourism booming, the country was still economically fragile. For the first time in the history of the country, Sri Lanka managed major budget primary surpluses in 2017 and 2018. The notoriously bureaucratic and inept public sector was bloated, and the army too large to sustain, but foreign investment (some as more debt) continued to flow into “the pearl of the Indian Ocean.” Despite everything, Sri Lanka still looked like a bet that could pay off richly. Even though dark economic clouds threatened on the horizon, disaster still felt easily avoided, or, at least, still a decade or more away.

Flag lowering at dusk on Galle Face Green, across the street from one of the bombing sites.

Then the dominos started falling. On Easter Sunday 2019, the suicide bombings hit and Sri Lanka’s image was immediately returned to that of a war zone in the eyes of international travelers. The threat frightened tourists away and the economy took a blow it would never recover from. Blaming the Sirisena government for the security failure (Indian Intelligence had warned them to be alert for the attacks before they happened, but they had failed to take the proper action to prevent them), Sri Lanka turned back to its war heroes of Mahinda and Gotabaya, electing Gotabaya as president in November 2019. Mahinda became his Prime Minister, and their new government immediately cut taxes in keeping with a promise Gotabaya had made during the elections.

Note, that was only about two and a half years ago, though COVID has made it feel like forever. The Rajapaksas went from conquering heroes to exiles in less than 30 months. It’s enough to send shivers up your spine how quickly their actual downfall came about.

Of course, the handwriting was already on the wall. COVID was just getting started and Gotabaya received a memo in May 2020 from his finance minister stating Sri Lanka would “experience a significant dip in foreign currency inflows by way of tourism, exports, and remittances (cash sent home from Sri Lankans working overseas).”[9] The memo went on to estimate that the downturn would be in the neighborhood of fifty percent lower revenue. At the time, foreign reserves were at about $7.1 billion, but commercial borrowing was up. It had been about $5 billion and made up about twenty-five percent of national debt in 2014, but had more than tripled to $16 billion and about forty-seven percent of what was owed by the end of the decade. The document was signed by Mahinda, and then by the Finance Minister. The memo outlined several things that could have been done to lessen the impact of this projected deficit, including freezing continued development projects (which had about $9 billion in undistributed funds), but none of the suggestions were followed.

It’s worth noting that this same year, the US had offered an aid package of $500 million with no strings attached other than the money being allocated to certain line items. One stickler for Sri Lankan politicians was $80 million to help clean up their property records, a huge gray area for many land “owners,” and one politicians have exploited for decades to commandeer land for themselves. Quick to insight conspiracies—as Sri Lankan writer Michael Ondaatje once wrote, “In Sri Lanka a well-told lie is worth a thousand facts”—the US money was deemed as “colonialist,” an attempt at making Sri Lanka indebted to them (even though it was aid money and not a loan), and eventually the offer was rescinded.

The Rajapaksas pressed on. In the equivalent to US midterm election in August 2020, beneath the shadow of the COVID pandemic, the country voted five members of the Rajapaksa family into parliament and their new political party, the SLPP, gained roughly a two-thirds majority. With this upper hand, the SLPP wasted no time in passing the Twentieth Amendment to the Sri Lankan Constitution in October, effectively repealing the nineteenth amendment and reinstating the eighteenth (I know, confusing). Control of the government was again consolidated in the office of executive president.

Going All In on Organic

Under the bright sunshine that makes Sri Lanka the natural wonder and paradise that it is, the country was in the midst of a financial monsoon that was rapidly eating away at dollar reserves, but, still, no one seemed to be paying attention. That was bad enough, but one more great blunder was on the way before things got really bad. On April 29, 2021, Gotabaya proclaimed that Sri Lanka would turn fully to organics and banned chemical fertilizers, effective immediately, planning to make Sri Lanka the world’s first fully organic farming nation.

Of course, the county was nowhere near ready for this change—something that takes somewhere from three to seven years to make effective, at best. In another inside deal, Sri Lanka ordered 99,000 tons of organic fertilizer from a Chinese firm, but when the first consignment of 20,000 tons came in, inspectors found it was tainted with plant pathogens that would have had serious ramifications for Sri Lanka’s biodiversity. The ship was not permitted to dock, the shipment was returned, and the order was canceled. Despite this, Sri Lanka was force to pay $6.7 million (seventy percent of the total price for the order plus applicable freight charges) to remain in China’s good graces.[10] Without fertilizers, the immediate result was reduced yields across the boards, some as severe as forty percent, and Sri Lanka was suddenly facing food shortages as soon as fall of 2022. The organic-only mandate was lifted in September 2021 after massive protests by farmers, but by all accounts, the damage was already done.

As shortfalls grew worse, Sri Lanka simply printed more rupees to pay salaries—by some estimates equivalent to $3.4 billion worth—which fed already out of control inflation.

The Last Straw: The War in Ukraine

Winter (a relative term here, because the weather is warm and humid all year round) is tourist season in Sri Lanka, and there was some hope tourist levels might get back to normal in 2022 with COVID hopefully running its course. However, two major tourist nations for Sri Lanka are Russia and Ukraine, so when war broke out in Ukraine, the rug was pulled out from under Sri Lanka once more. By this time, there were only a few more dominos in left for the Rajapaksas left to fall.

The war in Ukraine was only a few weeks old when we touched down in Bandaranaike International Airport, north of Colombo, on February 28, 2022. Naively, we were excited to begin Melissa’s ten months working to facilitate foreign direct investment (FDI) in ecotourism with a subcontractor to the United States Agency of International Development (USAID). That was the day we got our first glimpses of the Lotus Tower, our first exposure to Colombo traffic, our first sightings of tuk-tuks, and experienced our first sunset into the Indian Ocean. That feels like a lifetime ago now.

Things Fall Apart

The next domino fell about a week after we got here. No longer having enough reserves to sustain the exchange rate with the dollar, Sri Lanka floated its currency on March 8. The exchange rate immediately began climbing, going from 200 lkr (Sri Lanka rupees) to the dollar, then to 300, and finally settling around 360 lkr May 5 and thereafter. In less than two months, the rupee had lost close to half its value.

Looking across the sandy expanse of the Port City as it sits today.

Long before this, however, shortages of essential imports had already begun. Rolling blackouts because of the lack of diesel to run power stations swept across the country (some lasting as long as thirteen hours) in the later weeks of March. Prices for petrol, diesel, cooking gas (a mix of propane and butane), and food began climbing rapidly. In April it was announced that Sri Lanka could no longer keep up with its payments on their reportedly $51 billion in debt, and by the end of that month, she had officially defaulted.

In response to growing protests about the situation, in early April, the president asked for the cabinet to step down and invited members parliament to step up and help him form an all-party government. (From a semantics standpoint, the cabinet is “the government” as it is comprised of all of the different ministers who run the different departments of the government, thirty-one in all.) He would remain president and Mahinda would still be prime minister, but the rest of the cabinet (including three other Rajapaksa family members) would be replaced.

In the week or so to follow, parliament was locked in debate that was mostly a blame game and shouting matches, no one being willing to step up and take responsibility for helping fix things. There were calls for the Rajapaksas to step down, and fingers pointed in every direction. No one was talking of joining a new government and many declined stating they would never join forces with that powers in place. With no one apparently willing to join the new cabinet, Gotabaya reshuffled the deck as best he could. A group of three new finance managers were appointed to negotiate with the IMF for funding to sustain essential services while India stepped in with a line of credit to help Sri Lanka buy fuel. None of that would make much difference on the ground, however.

Protests began mildly soon after we arrived. Except for one incident early on when police lost control near the President’s House and an area upcountry where a protestor was shot when the group he was with refused to unblock an intersection, protests remained peaceful. The catchy slogan “Go home, Gota” became a rallying cry, and a tent city of sorts was set up between Galle Green and the Presidential Secretariat across Galle Road (the main road along the seafront) from the Port City. The area took on a festival atmosphere of sorts and became known as “GotoGoGama.” It was a popular after-work hangout: a place from which to shout together, watch impromptu theatre or dancing, peruse the makeshift library, release some steam, listen to protest speakers on the weekend, and the like.

Black Monday

When things didn’t improve, Gotabaya decided to reshuffle the deck again in the cabinet, only this time he would ask his brother to step down as Prime Minister as well. This was on Monday, May 9. As Mahinda was resigning, SLPP supporters were bussed in to Colombo and marched through the streets armed with iron pipes and other weapons to Temple Trees, the government residence of the Prime Minister. When they arrived, they unleashed their anger on the peaceful protestors. From there, they moved to GotaGoGama and began setting fire to tents and chasing the anti-Rajapaksa protestors from the area. A quick backlash spread across the country and into the night. More than seventy government officials homes were set fire to that evening. Hundreds were hospitalized and nine were killed, including a SLPP MP and his body guard who opened fire when their car was blocked. The day was quickly dubbed “Black Monday.”

What felt like the beginning of a civil war to the rest of the world was a momentary blip here, however. Things seem back to “normal” the next day. Mahinda fled with his family and went into hiding at the naval base in Trincomalee, and the protests returned to a slower grind with a returned festival atmosphere. Petrol queues continued to get longer, however, and become more of a common thing as tankers would anchor off the coast and then leave again without unloading because they weren’t paid. (In a small country where everyone seems to know when the next shipment is coming it, each of these was felt like a collective sigh of despair.)

In the days following Black Monday, the president appointed Ranil Wickremesinghe to be the new Prime Minister, which would be his sixth time taking the office. This new Prime Minister then did his best to form another “all party cabinet” from the same deck of cards. About this time, government workers were given Fridays off to stay home and plant personal gardens to help against the predicted coming food shortfall.

As grocery store prices multiplied, people were reducing the number of meals they ate each day. Kids were home from school because of the lack of transportation, so at least families could eat their one meal a day together.

Cricket to the Rescue

An editorial after they won the Asia Cup a couple months later.

Then, somewhere in the weeks to follow, it was as if all of this was forgotten when Australia came to Sri Lanka for three series of cricket matches that would be played in various parts of the country. The joke was that the only longer lines than the petrol line was to get tickets for these cricket matches (though a longer, more difficult to see queue might have been the one at the emigration office as Sri Lanka’s sought to live elsewhere in the world). Australia won the initial T20 best of three, then Sri Lanka won the longer five day 3-2, and a subsequent five day in Galle was halted at 2-2. For a minute, it felt like things could feel a little more normal and people could just have fun dancing in the stands and hoping to get on the stadium big screen. The Australians were recorded saying they had never been cheered for by the people of the opposing country as they had in these matches. Sri Lanka was sincerely grateful for the courage they had shown in coming when the rest of the world was staying away and labeling Sri Lanka as a dangerous place to be.

But shortages persisted, as did the protests. Empty blue cooking gas canisters were lined up all the way around the cricket stadium in Galle during the final matches with Australia so the world could see what was going on. Impossibly long petrol and diesel queues grew even longer. By July 4, the fuel shortages looked so bad the government issued a decree that only essential vehicles would get fuel until July 10. They were hoping to get another tanker in the following week and then one more before the end of the month, and that was it. Things were going to be scarce for some time.

Tuk-tuks lined up for petrol.

It’s worth also noting that the petrol and diesel queues had become a bit of an art form by this time. It was also the new social gathering place. When they first began, these lines were a tangle of vehicles coming from every direction into the pumps. These slowly transformed into better organized lines that were only distinguishable from a row of parked cars by the fact that there were drivers in all of them. Then people began to gather outside of their vehicles and commiserate. Then as fewer cars were on the road, queues began to parallel one another. On the inside, against the curb (if there was one, in not, on the side of the road) were the cars. Just outside of that, the tuk-tuks lined up in all of their primary colors. Outside of this were the motorcycles and scooters. These often took up an entire lane, but what does that matter when there is less than a third the normal traffic on the roads? Then imagine these rapping around blocks or extending for miles, and people going from hours waiting in these lines to days. In the Sri Lankan heat, these are painstaking ventures. Eventually reports surfaced of deaths while people were waiting in line. One man gave in to exhaustion and died the next day while at home. And, of course, this is only half the line. Out the other side of the station would be the diesel queue, just as long if not longer, but in single file, made up of vans, busses, trucks, and construction equipment—whatever runs on diesel short of the power plants and personal generators.

The Arab Spring and Jan 6 All Wrapped into One: July 9

All of that led to the last two weeks. Word on the street was there would be large protest gatherings on Saturday, July 9, the two-month anniversary of Black Monday. On Friday, July 8, the government announced an open-ended curfew for 9:00 pm that evening, hoping to discourage people from traveling to the protests. Under pressure of from the bar association and other parties, the curfew was lifted the next morning though at 8:00 am. The paper the day of the protests had several articles with politicians defending people’s rights to peaceful protest. There was even an article from the president trumpeting the recent success of the government to get much needed medical supplies, promising new fuel shipments by July 12, and encouraging people not to fall of misleading statements by opposition groups whose efforts to discredit the current government saddened him. (Oh, if only!)

Of course, by all accounts, by the time that paper reached doorsteps, he was already aboard a naval vessel sailing away from Colombo for safer waters.

While the events of July 9 could have easily turned into more bloodshed than was seen on May 9, the vast numbers of Sri Lankans who gathered seemed to meet restraint rather than resistance. After trying tear gas and water cannons to keep protestors from entering the empty official President’s House (in which it was reported that the president wasn’t even sleeping in these days), once the tide broke over the fence, security forces let the protestors have their way. People streamed into the building, raided the presidential candy stash, cooked snacks in the kitchen, took over the workout room to walk on the treadmills, swam in the pool, jumped on the bed, and even reportedly used the presidential showers. It was like watching kids party while someone’s parents were away. Comic, save the implications of just having topple their own government out of sheer mob energy.

After crashing their way into the President’s House and the Presidential Secretariat near Galle Face Green, attention then turned to the president-appointed PM, who agreed he would step down as well if the president did. In response to his concession, Temple Trees was infiltrated and occupied as well (where the PM was not living at the time), and his personal residence was set fire (where he had been living at the time).

The next day, these building remained open to the public to peruse and wander through at will, armed security forces merely standing by and watching as people trailed in and out like it was a free day at the museum.

By the end of the weekend, the president said that he would step down the following Wednesday, July 13. The hope became he would step down, as well as the PM and the rest of the cabinet, then the parliament could gather to elect an interim president and prime minister, and they could make a third attempt at creating an all party government. (Just how you do that differently when two-thirds of the seats still belong to SLPP members is unclear, but that was the hope being expressed.) Whether protests would reignite if protestors weren’t any happier with this new government than with the old one still remains to be seen.

In the end, Gotabaya put a condition on his resignation on Wednesday morning. He wanted his family to be allowed to leave the country safely first. Waiting for that, he did not resign, even though he had already fled the country to the Maldives. (And, I might add, if you’re going to flee a country, the Maldives is a great choose to relax and get your thoughts together before you head to a more permanent destination.) Regardless of his lack of official resignation, Ranil Wickremesinghe was named acting president, much to the chagrin of the protestors as they saw him as a patsy of the Rajapaksa government. In response, they breached the Prime Ministers offices to show their displeasure, and Wickremesinghe proclaimed a curfew to curb further destruction of public property. Curfew expired the next morning, but was reimposed again on Thursday from noon to 5:00 am on Friday.

It wasn’t until late on Thursday, having moved on to Singapore by then, that Gotabaya Rajapaksa finally broke up with Sri Lanka for good via email. Triumphant, in the hours that followed, protestors left the Prime Minister’s offices and the President’s House they had been occupying (cleaning up before they left, it should be added), and a new measure of hope seemed to permeate the air that Sri Lanka’s could go back to living in denial of their circumstances. (The protesters have yet to leave the Presidential Secretariat, however, where they moved their tent library. Many of the donated books have been marked “#GoHomeGota2022 Library.”[11])

Post Rajapaksas

None of this, of course, would pay for fuel that is still desperately needed, or restore needed imports of food and medical supplies, but at least if they can get a new government situated before the end of the month, hopefully negotiations with the IMF for gap funding can get underway again and some hope of progress be made before the food shortage begins to take real effect in the coming weeks. Parliamentary elections for a new president and PM took place on July 20 (the day after I originally wrote this blog) and Ranil became the new President, and he appointed is own new Prime Minister. Every other member of the cabinet remained the same.

Those who remain in parliament are still cut pretty much from the same cloth as the Rajapaksas, only aren’t as good at the power game as they were. Or, actually, It might be said that Ranil is better. In the months since taking the helm, there have been no new protests worthy of mention basically because they have made sure there weren’t. Many who led the old protests were arrested and intimidated—er, I mean, interrogated (or do I?). The tent city of “GotoGoGama” was dismembered by riot-gear wearing police in the dead of night. Despite objections voiced by external human rights groups and the Sri Lankan Bar Association, “law and order” were restored, making room for now loan arrangements to be made to get the power, petrol, diesel, and gas flowing again, and while many aren’t quite appeased, a more routine way of life has returned to the streets as everyone looks forward to the coming tourist season that picks up on November and runs through winter for the countries of Europe and those north of this not-so-small tropical island.

Regardless of its ghosts, it’s still hard to beat the serenity of this “resplendent island.”

Recent history hasn’t exactly borne out hope for things getting better after all that has transpired here in 2022, either. Better things didn’t happen to any of the countries who experienced an Arab Spring and no one is looking to January 6 as an example of democracy at its finest. As things stand, jostling for power continues in the vacuum left by the president’s resignation. (In fact, not long after Gotabaya returned to Sri Lanka in the dead of night, he began working to clean up his image. Does he possibly hold a glimmer of hope he could get back into the game after all that has transpired? Some suggest he might.)

There are no clear leaders to blaze a path out of this mess. Trade imbalances will not go away any time soon, and any normalization that has occurred in recent months is simply the result of getting more loan money flowing into the country. Unless this tourism season really picks up toward pre-2019 bombing levels, all they have presently done is kick the can of everything come due at once again down the road a bit.

There are fundamental changes needed in the governmental culture here that even a new constitution will not fix. A problem with socialism is that when the company that runs out of money for essentials goods is the government, then the government is broke, whereas if it were a business, that business could close up shop and its competition would take its place. Here, when the government fails to meet its responsibilities, there’s no one left over to fill the gap except a foreign power, and nobody wants that.

Interesting times, indeed, but also “more open to the creative energy of men (and women) than any other time in history” as well. Here’s hoping for the latter. In my few months here I’ve learned to marvel at the ingenuity and artistry of the Sri Lankan people as a whole. Here’s hoping for the Sri Lankans on the street to show the same energy in helping each other that was shown in gathering in huge numbers on July 9. Let’s hope for food production to again to the point or self-sustainability. Here’s hoping for a wave of innovative Sri Lankan entrepreneurs to grab ahold of the problems rising and answer then in creative ways. Sri Lanka is still a gem of an island with so much to offer the rest of the world. I mean, Portugal once made a fortune exploiting this island, as did the Dutch and the British who followed—if only they could do the same thing for the sake of all Sri Lankans instead of an elite few.

Here’s hoping in the people on the ground who stood up for themselves to stand up for each other now in the streets and the towns and the villages. It might be the best hope Sri Lanka has at the moment for closing this chapter of its history and starting a new one. It’s time to show the ghosts a better way. Here’s hoping.

[1] Robert F. Kennedy, “Day of Affirmation Address, University of Capetown, Capetown, South Africa, June 6, 1966,” John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum website, https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/the-kennedy-family/robert-f-kennedy/robert-f-kennedy-speeches/day-of-affirmation-address-university-of-capetown-capetown-south-africa-june-6-1966. (It also appears that there is no such Chinese curse, but it’s still an intriguingly ironic thought.)

[2] Eelam is the Tamil equivalent to lanka, which is the name of this island; like as Tamil Nadu refers to a Tamil state in India, the tigers hoped they would have a Tamil state on this island as well.

[3] Rory Spowers, A Year in Green Tea and Tuk-tuks (London, UK: HarperElement, 2007), 152.

[4] Deborah Brautigam and Meg Rithmore, “The Chinese ‘Debt Trap’ Is a Myth,” The Atlantic (February 6, 2021).

[5] “Foreign Financing of the Budget: Performance Report 2007 (PDF) (Report),” The Department of External Resources, the Ministry of Finance and Planning, 2008, http://www.erd.gov.lk/images/pdf/performance_report_2007.pdf (accessed, July 19, 2022).

[6] Rajeev Sharma, “Rajapaksa Family Stands To Receive In Commission Anywhere Between US$1.2 To US$ 1.8 Billion During 2005-15,” Colombo Telegraph, October 27, 2012, https://www.colombotelegraph.com/index.php/rajapaksa-family-stands-to-receive-in-commission-anywhere-between-us1-2-to-us-1-8-billion-during-2005-15/ (accessed: July 19, 2022).

[7] Yogesh Gupta, “China’s infrastructure projects have worsened Sri Lanka’s economic woes,” Deccan Herald, June 1, 2021, https://www.deccanherald.com/opinion/china-s-infrastructure-projects-have-worsened-sri-lanka-s-economic-woes-992445.html (accessed: July 19, 2022).

[8] Hirantha Herath, “Colombo Port City: Wake up, dream on to reality – Part 1,” Sunday Observer, July 4, 2021, https://www.sundayobserver.lk/2021/07/04/opinion/colombo-port-city-wake-dream-reality-–-part-1 (accessed: July 18, 2022), and Anbarasan Ethirajan, “Colombo Port City: A new Dubai or a Chinese enclave?” BBC News (January 17, 2022), https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-59993386 (accessed: July 13, 2022).

[9] __________, “Gotabaya Govt. got early warnings about economic crisis,” The Sunday Times, July 17, 2022, 1.

[10] Neil DeVotta, “The Rajapaksas to blame for Sri Lanka’s disastrous 2021,” EastAsianForum, January 19, 2022, https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2022/01/19/the-rajapaksas-to-blame-for-sri-lankas-disastrous-2021/ (accessed: July 18, 2022).

[11] Bhavya Dore, “Sri Lanka’s Presidential Secretariat Is Now a Buzzing Library Overseen by Protestors,” The Wire, July 20, 2022, https://thewire.in/south-asia/sri-lanka-presidential-secretariat-library-protestors (accessed: July 20, 2022).

Excellent Summary. And a tough read. I feel for the people. I recently did a long assignment in Nigeria and later on, Cameroon. Same story – different people.

Thanks, Jim! I’m going to updated it soon as well. Things have settled a little, but remain “interesting.”

Will this be a published book?

No immediate plans. I just wanted to let friends and family know what was really happening here. 😁