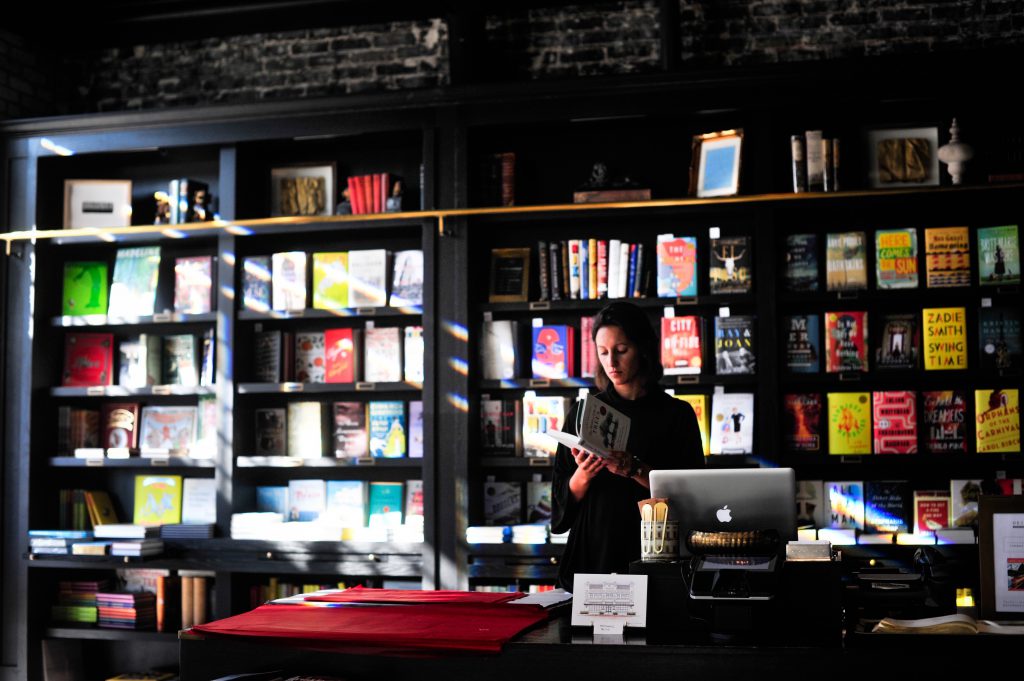

Picture by Pj Accetturo on Unsplash.com

Yeah, I know you’re not supposed to do that, but far too many authors underestimate the power of the physical design of a book. Today more than ever, the look and feel may not tell you much about the quality of writing or depth of thought put into a book, but they do tell you a lot about how much the author and/or publisher were willing to invest in the message. And if someone’s not willing to put a quality cover on a book, how much time, effort, and editorial effort—usually by far the most expense part of publishing a book—were they willing to spend on what’s in the book?

When you consider that, then maybe taking a second look at the cover of a book—especially if it is the cover of your book—is something you should give more thought.

Now, let me say up front that, yes, I am a bit of a book snob. I love books, I love old books, and I love books that are done well—books that feel like books and that have their messages dictate their design from typestyle to cover art and treatments. Books with unique formats often get notice before other books, and sometimes noticed enough to get bought. (E-books, eat your hearts out!) And it’s not just the cover—it’s also the trim size, the quality of paper, the little pictures on each title page (or whatever other features are included)—everything that goes into making the book a book.

To give a specific (though a bit an exaggerated) example, have you ever seen a DK book? If you’ve seen one, you’d know another instantly. While they are more varied now, all of the first ones followed this basic design. Once you enjoyed looking at one, you would automatically pick up another when you saw it—even just to page through it and see what it was about.

Another example would be the check out the bestseller, Essentialism by Greg McKeown. Notice how the interior design matches the cover and contributes to the message of the book. Sharp, simple drawings go a long way to telling us what Essentialism is about.

Speaking of Essentialism, the next time you go to a bookstore try this little experiment: go to the business leadership section (or whatever your local bookstore calls it) and take find a copy of Essentialism and any titles by Malcolm Gladwell, Pat Lencioni, and line them all up next to each other. See a pattern? They are what are called jacketed, trade-sized hardcovers. See if you can find others using the same trim size in the same section, and then see where you can find similar designs elsewhere in the bookstore. (Check the memoirs and biography sections, for example, or health and fitness.) Do you think someone found a conventional size and page length that appeals to business types?

If you look closely, you’ll begin to see a pattern in each section of the bookstore. Is it that books of a feather flock together? Or is there some marketing expertise to what kind of cover and trim size best fits each book?

In the same way that certain word counts go with certain genres, certain book designs do as well. (Of course, it’s a bit of a trick to fit in with these conventions and stand out at the same time, so sometimes that’s about the interior design—think of Essentialism and a book like The One Thing or Rework as examples of doing both interior and exterior well.)

Each trim and different type of paper says different things to a potential reader. Mass market paperbacks say, “Read me on the beach.” Six by nine hardcovers say, “This is a book of some substance” (especially if they are over 300 pages long). Books taller and wider than six by nine say they are for reference or are workbooks. Picture books and coffee table books go even bigger, trying to be their own works of art to match the art within them. Sometimes the size, heft, and shape of a book can tell you as much as the jacket copy does—and does it without potential readers even noticing.

As an editor and ghostwriter who has done dozens of books of varying success, I’ll be the first to tell you that good content is, as a rule, not nearly enough (of course, there are huge exceptions to this where it was indeed exceptional content that got a book noticed—take the 35,000 e-book copies of The Martian Andy Weir sold before Random House and Fox Pictures started calling). At the same time, we still like books that speak to us as books—which is also perhaps why physical books seem to be making a comeback over e-books. We like books that look like books that some designer gave some thought to.

Another thing to think about is that there is really no reason to make an ugly book today. Technology has made publishing accessible to practically everyone, but wrenching the controls out of the hands of the gatekeepers has not been beneficial to everyone. Technology has made creating good-looking books accessible, but many, for the sake of saving a couple hundred dollars, get swayed by “publishers” (at least that is what they call themselves, they are really just “printers” who offer à la carte editing and design services) to have their books made in the publisher’s one-size, one type of paper, one format (which is usually pretty airy since that makes the book longer and they can charge you more), paperback-fits-all style that looks like every other self-published book they have even made no matter the cover art or what logo you put on the spine. You’ve seen them—I don’t even have to tell you the self-publishing, print-on-demand services that cough them out. Ugly, blocky, trade paperback books that look like bricks (at least they do to me). Few, if any, cover treatments (though “glossy” is a favorite). Go anywhere a lot of self-published authors are promoting their work and you will see them by the dozens—and for some reason, you see very few on the shelves of bookstores.

That should tell you something, shouldn’t it? Why would an avid, knowledgeable reader settle for reading something that looks more like a brick than a book?

Content is king, you will say. I heartily agree—but kings who get ignored don’t have much influence. I have books that have sold in the hundreds of thousands and books I feel I did a better job on that have sold dozens. Sure, there were also marketing issues that made a difference, but I’ll also tell you that quite often the books that didn’t sell didn’t look like other books in their genre. Would getting that right have made a difference? I can’t say for sure that it would have, but I also know the difference between success and failure isn’t decided in multiples, but in increments (look at the difference, for example, of the time spread between the first and fourth runner in an Olympic final of the 100 meters—one gets the gold, the other gets nothing—and in business the difference between first and second is usually the difference between success and failure, between a purchase being made or not).

As an author, you need to give your book every advantage you can. The difference between 95 and 98 percent may not seem more important than the difference between 50 and 95, but it’s that final three percent that can mean someone seeing, picking up, and buying your book—or someone just walking by.

So beware anyone who promises you the moon if you just get your book into print. There’s a lot more to publishing than that, and the fact that they can publish your book cheaper than anyone else (within reason of course—you can spend big money on a book and still get it wrong) is almost literally a promise that you will be throwing your money away. Sure, like I said, there are exceptions, but those are the lottery winners because of extraordinary content—and things that happen about as often as someone winning a mega-jackpot. And, in some cases, it’s better to go inexpensive first to get something into print you can build on for your next book—but it needs to be part of an overall plan to build your business as an author and whatever other subject expertise you are selling.

Of course, maybe there’s something besides printing copies of your book that would be better to do first, like using that material to build your audience—but that’s a blog post for another day. 🙂

Recent Comments